nameless beauty

River and Waterfalls Along Djupavogshreppur

River and Waterfalls Along Djupavogshreppur

We notice in the distance a few cars pulling off to the left of the road, drivers hopping out in swimsuits in piercing cold, gingerly stepping along graveled paths. Glacier-melt river meanders along the edge of the Ring Road as we pull over to explore, well zipped up in our insulated coats. Greg walks along the riverbed hiking close to the waterfall where hearty swimmers disappear beyond steep vertical cliffs obscuring the cascading waters. He balances carefully on rounded boulders, as I do the same walking in the opposite direction to get a wider view of the river and turquoise falls peeking out from the precipice. We are unrepentant in our obsession with waterfalls and undeterred by repeated stops to get our fix. I search the guidebooks, and later the Internet, to find images and a name for this beautiful falls and roadside river to no avail. The only information is the GPS tag on my cellphone: Djupavoshreppur. So many waterfalls, so little time, and I realize as I write this post, so few names to encompass this ever present beauty. I think about the joy of being near creeks as a child – I don’t remember their names either. Catching frogs along the creeks feeding Mendon Ponds, then later playing along Irondequoit Creek in Ellison Park. Now I live across from Second Valley Creek. I wince at the lack of imagination for the geology of my current neighborhood. First Valley and Second Valley are the places names of our town. First Valley Creek and Second Valley Creek the names of our lovely waterways on the Tomales Bay watershed. Possibly nameless beauty is a kinder way.

Folaldafoss on the Oxi Pass

Folaldafoss on the Oxi Pass Zoom Lens of Cerulean Pools

Zoom Lens of Cerulean Pools Land Falls Away Into Water

Land Falls Away Into Water Austerlands Fyodurs Wrap Around Mountains

Austerlands Fyodurs Wrap Around Mountains Austerland tributaries & mudflats stretching out beyond Vatnajokull

Austerland tributaries & mudflats stretching out beyond Vatnajokull

Jokulsarlon Glacial Lagoon in June 2017

Jokulsarlon Glacial Lagoon in June 2017 Colors of blue at Jokulsarlon Glacial Lagoon in the middle of a snowstorm in June.

Colors of blue at Jokulsarlon Glacial Lagoon in the middle of a snowstorm in June. Glacial Outwash of Skeiðarársandur in the Southeast

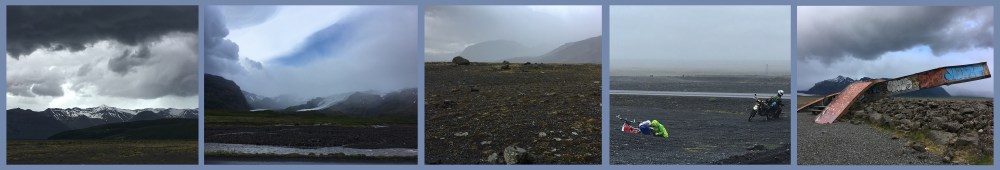

Glacial Outwash of Skeiðarársandur in the Southeast Arctic winds scour the sandur with fierce winds amid isolated farmsteads, calving glaciers, bowed tourists, and ruined bridges.

Arctic winds scour the sandur with fierce winds amid isolated farmsteads, calving glaciers, bowed tourists, and ruined bridges. South Shore on the outskirts of Rangarping Eystra

South Shore on the outskirts of Rangarping Eystra